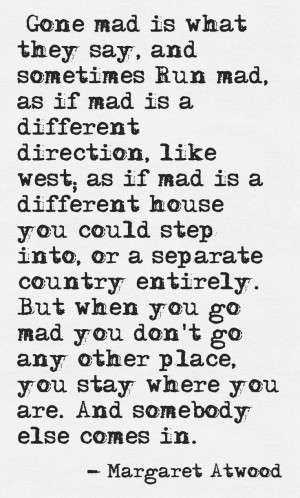

Upon the father’s request that his daughter “write a simple story just once more” (756), the daughter-narrator composes a story, which along with their conversation about it, yields the same variations on conflict presented in Atwood’s “Happy Endings” (with B, C, D, etc.), plot propelled by a character’s internal conflict, by a character’s conflict with another character, and by conflict with fate. That approach makes “Happy Endings” more self-consciously metafictional than Paley’s “A Conversation with My Father.” (29) Grace Paley’s Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (1974) / Ītwood’s narrator keeps her distance both emotionally and spatially from the stories she tells, neither becoming a character nor inviting her readers to step into her characters’ lives. That’s about all that can be said for plots, which anyway are just one thing after another, a what and a what and a what. True connoisseurs, however, are known to favor the stretch in between, since it’s the hardest to do anything with. Instead, the narrator asserts that the only authentic ending is death and concludes with these lines: In the end, Atwood’s narrator doesn’t return to the happy ending of A, though supposedly all of the letter-labeled variations on plot lead back to it. Instead they struggle against a force of nature, namely a tidal wave-until, at the end of the story “inally on high ground they clasp each other, wet and dripping and grateful, and continue as in A” (28). Subsequently, D’s plot develops not from the couple’s issues with each other or their internal conflicts. The couple at the center of D “have no problems,” the narrator tells us. Both John and Mary have other partners, and their story develops not only from the conflict between them but also from their internal conflicts: Mary loves James but sleeps with middle-aged John out of pity while John, despite his love for Mary, cannot bring himself to leave his wife. In C Atwood’s narrator offers another story of unrequited love but with more complications. The story reaches a crisis when Mary’s friends tell her they’ve seen John in a restaurant with another woman. It’s a story, not merely an anecdote, because John and Mary’s opposing desires complicate their relationship: Mary wants love from John John wants sex, not love, from Mary. In B, Atwood’s first story-within-her-story, the narrator chronicles unrequited love as the source of the conflict essential to plot: “Mary falls in love with John but John doesn’t fall in love with Mary” (27). Margaret Atwood’s Murder in the Dark (1983) / Ītwood’s story takes the form of templates, beginning with A, a happy ending, followed by variations on plot, labeled B, C, D, and so on, that purportedly lead back to A. That discrepancy between art and life forms the basis of both Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings” and Grace Paley’s “A Conversation with My Father.” Though stylistically different works of metafiction, Atwood’s how-to guide and Paley’s autobiographical dialogue similarly explore the limitations of plot structure and the artificial quality of endings. Stories look like life, but our daily lives don’t follow the pattern of fiction. Two days before my students’ drafts are due, I have an additional model for them. That’s the trouble with deadlines: We have to meet them, ready or not.īut that trouble with deadlines also calls attention to the usefulness of imposing earlier deadlines–pre-deadline deadlines–as hard as that is. Why did I give my students the earlier less-polished version? Because I wanted them to have my model in hand a week before their own drafts were due. “It’s a serviceable draft”, I told them, “it gets the job done, but it could be better.” This version is better, but it’s still a draft or two from where I’d like it to be. Last Thursday, when I gave my students copies of the earlier version as a model for their comparative analyses, I said it was still a work in progress, that there were additional changes I wanted to make. The revision, posted October 21, omits many of the plot details of the earlier one and develops the examination of the three types of conflict that Atwood and Paley depict. The blog entry that follows differs notably from the version I posted on October 17.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)